Scale Ain’t What It Used To Be

Prior to these three forces of Abundance, Access, and Automation teaming up to inflict massive change on the world, the primary method an organization had to stave off competition and achieve sustainable success was to reach scale. Once you were big enough and had enough existing customers, it was damn hard for a competitor to come in and knock you out. Because you produced such large quantities, you were able to offer your product at extremely cheap prices. No new startup could offer something at that price and hope to turn a profit. And it’s not just that your production process was big; it was the perfect balance of lean and complex. You effectively managed throngs of international suppliers so that each part of your operation was conducted at as low a cost as possible. It would take years for a new upstart to develop the international relationships and physical infrastructure necessary to compete!

“Disruptive Innovation”

But then upstarts began doing exactly that. In the mid 90’s, Clayton Christensen, renowned business professor at Harvard, began to notice that large industry incumbents were starting to be dethroned by upstarts that never should have had a chance. Christensen called this “disruptive innovation” and offered a framework for understanding it. He described the pattern he saw as new competitors entering the market with a low-end, lower-priced product. The incumbent ignored them because they saw what the upstart was doing as having less profitability. Over time, though, the upstart’s product got better and better, and eventually, they became the new market leader by offering a product that appealed to the majority of the market at a cheaper price. Netflix “disrupting” Blockbuster is a classic example. And thank goodness. As fun as it was to walk the aisles of Blockbuster, praying that movie we wanted to watch was there, we love being able to just watch Netflix and chill.

Recognizing they were in serious trouble, large organizations began to clamor for a solution so that they too wouldn’t be disrupted by an upstart. Christensen found that because those organizations’ missions are focused on increasing stock prices in the short term, they consistently made the same mistake of not pursuing the lower margin product and eventually got disrupted. His solution was for large incumbents to “disrupt themselves.” Their only hope was to actually create and fund (and therefore own) the startup that was destined to disrupt them.

This solution, while potentially effective, offers a number of problems. First of all, the managers in charge of funding this internal startup face the same pressures to maximize short-term shareholder value. They have every incentive to take the potential budget for this startup and instead funnel it into producing an extra hundred widgets that sell at a higher margin. Secondly, the “disrupt yourself” strategy, while potentially averts disaster for shareholders, is still a catastrophe for the organization itself. The original organization (and all the jobs it provides) still gets destroyed. The only consolation is that the startup that destroyed it happens to have the same owners (but try telling that to the line worker who lost her job).

Theory of Evolution

A better solution tackles the root of the problem: the organization’s purpose. The organizations that get disrupted focus more on profit than helping their customers. This is why, even though Blockbuster saw what Netflix was doing, they were afraid to pursue their own streaming service; they thought it would have lower profit margins. Organizations that successfully avoid disruption have an entirely different kind of purpose. Their goal is to come up with something specific to make their customers’ lives better.

Mary and Tom Poppendieck, leading authors on lean and business transformation, have found that the first priority of organizations who successfully avoid disruption is the lives of their customers. And it turns out that their shareholders' lives aren’t even the second most important thing. Nope, second is the lives of their employees. Shareholders are all the way down the list at number three (my oh my how the tables have turned).

Similarly, Harvard Business School professor and author Rosabeth Moss Kanter has found that organizations that focus on customers first (and shareholders last) don’t just avoid disruption, they are actually MORE profitable than their shareholder-prioritizing peers. Why? Well, the short of it is that they make long-term decisions, which manifests itself in two ways. First, they are always trying to find better ways to serve their customers regardless of whether the new way has lower margins. Secondly, long-term thinking manifests as a desire to survive. These organizations know that if they want to keep making an impact on their customers’ lives, they need to be around tomorrow, and the day after that, and so on. If sacrificing a few dollars today will ensure that they live on to fulfill their purpose in the future, they’ll make that choice every time.

Organizations formed around a purpose don’t get disrupted and they don’t “disrupt themselves.” They “evolve themselves,” continually changing and improving how they operate.

The Evolution of Netflix

Netflix began its purpose of delivering entertainment by literally delivering entertainment. They eliminated the drive to the store and the agony of not finding the movie you wanted by sending DVDs (remember those things?) through the mail (which is apparently still a thing?). As everyone began to sign up, Netflix was on top of the world (or at least their market). This meant, though, that they were at risk of being disrupted. So what happened next? Sure enough, that market went through two more radical transformations: the shift to streaming and the production of original content. In both cases, Netflix led the charge. And it’s not because they “disrupted themselves.” No, they were constantly looking for the best way to deliver entertainment to their customers. Streaming meant their customers wouldn’t have to wait for the next DVD to arrive in the mail, so Netflix did it. Producing original content meant that their customers would have higher quality choices, so Netflix did it. What they did not do was make short-term decisions to protect their very successful mail-order DVD business model. It was important that they make money so they could continue to serve their customers, but how was of secondary concern. That lack of rigidity meant they had the flexibility to evolve, and this evolution has lead to even more people signing up (or at least to find a friend with an account).

Viewed through this lens, what happened to Blockbuster wasn’t an upstart that happened upon and pursued a new technology. A new competitor did enter the market, but not with a purpose of profit, rather with a purpose of delivering entertainment to their customers. Because that was their goal, they found a better way to do it, and like a moth to a flame, the market quickly flocked to Netflix - and has stayed there decades later.

Evolutionaries

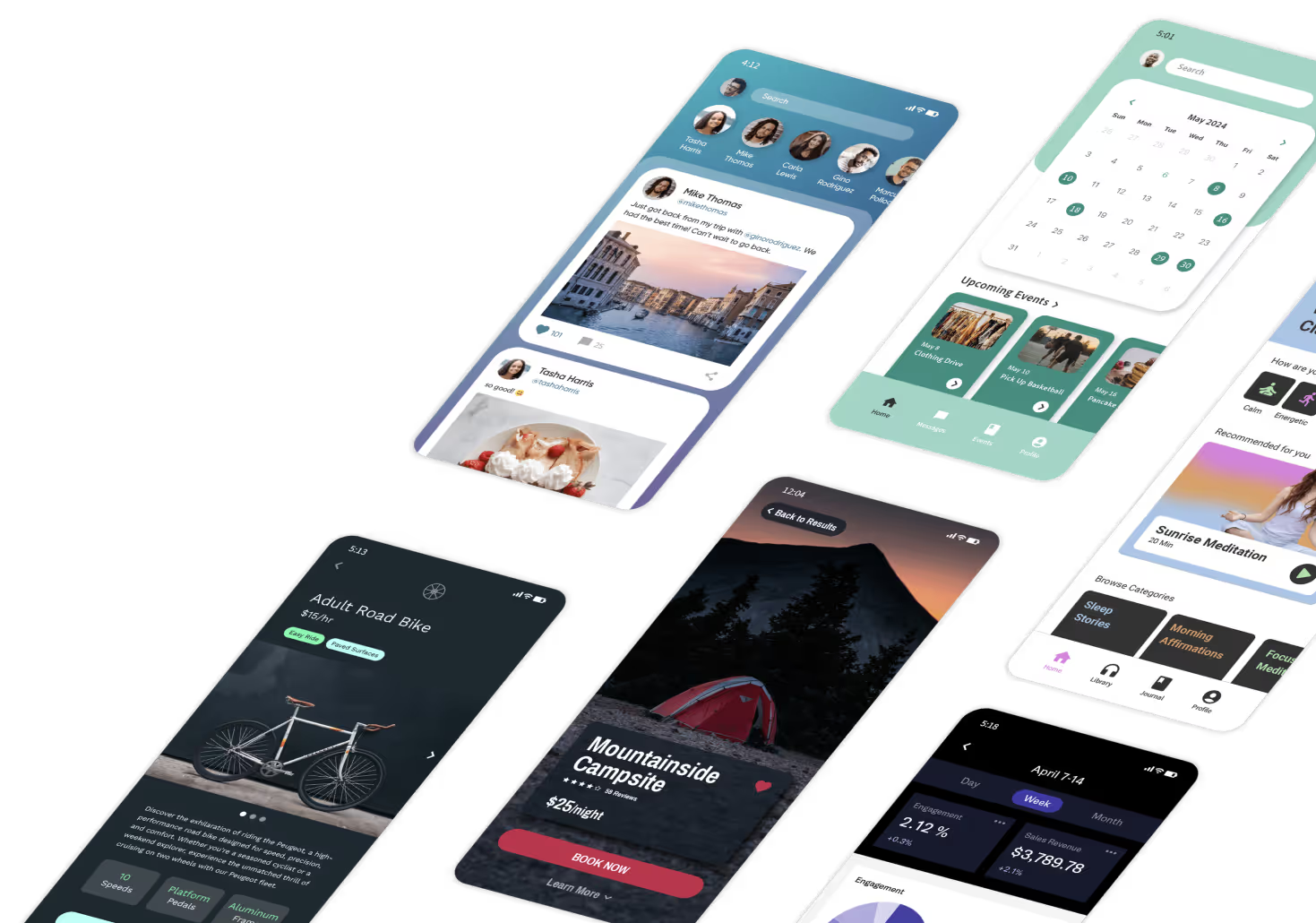

What does it mean to create an organization with the ability to evolve? The answer, which should come as a surprise to none of you, is to hire and train more designers and innovators. People with these skills are constantly finding better ways to serve your customers. That’s what evolution means to an organization. As more and more organizations come to this inevitable realization that the ability to evolve is the only real sustainable competitive advantage in today’s world of abundance, connectivity, and automation, they will be looking to people who know how to design and innovate to help lead the way. Will you be ready?

.png)

.png)

.png)